Surviving in an Alien Environment: Human + Christ as Medieval Natural-Born Cyborg

This is a guest post by Ruth Evans, a medievalist with the Department of English at Saint Louis University, Missouri. I know Evans through her fantastic essay Our cyborg past: Medieval artificial memory as mindware upgrade. If she hadn't contributed this essay I'd have used that one as a weekend reading piece. If I were you, I'd read both.

I have become fascinated by the idea of yoking together two apparently quite disparate ideas in order to get more closely at a historical understanding of both cyborg technologies and medieval identity. One is the hypothesis made by Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline in their seminal essay Cyborgs and Space (1960) that yoga and hypnosis are forms of cyborgian adaptation that might be used to promote survival in the alien environment of space. The other is a highly suggestive remark made by Myra Seaman in her article Becoming More (than) Human: Affective Posthumanisms, Past and Future (Journal of Narrative Theory 37.2 (2007): 246-275), namely that medieval people "examined and extended their selfhood through a blend of the embodied self with something seemingly external to it – not the products of scientific discovery, but Christ."

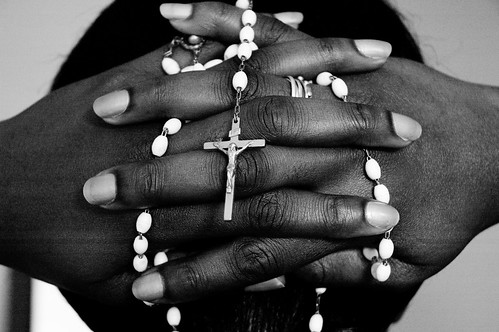

photo credit: A.CurrellI love the bold way in which Seaman imagines the human-Christ symbiont as a posthuman self avant la lettre: "a hybrid that is a more developed, more advanced, or more powerful version of the existing self." This suggests to me – though Seaman does not argue this – that in becoming one with the non-human prop of Christ, medieval persons extended their capabilities and were in turn profoundly transformed by that encounter, in a manner analogous to modern forms of distributed cognition: their minds, in other words, did not end with their bodies but were imaginatively and practically enmeshed in, and extended by, the external tool of Christ.The medieval historian Caroline Walker Bynum asks, "Are we genes, bodies, brains, minds, experiences, memories, or souls?" (2001, 165), but this misses the point. We are all these things, but we are also – and always have been, according to the cognitive philosopher Andy Clark – more than these things. We are all these things plus the non-biological technologies (writing, computers, cellphones, Christ) that enable us to adapt to our changing environment and to better survive as humans: we are, in Clark's words, "natural-born cyborgs" (and see further my essay: Our Cyborg Past: Medieval Artificial Memory as Mindware Upgrade, postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies 1/2 (2010), 64-71). Think not so much of the woman with a cochlear implant as the woman sitting in Starbucks with an iPad – or (as I will develop here) the medieval Christian joining with Christ.I'm not thinking of the physical ingestion of Christ's body in the Eucharist but rather of the many devotional and meditative practices – imitatio Christi [imitation of Christ – the emulation of his suffering, for example], embracing and kissing statues of Christ, meditating on his body – through which medieval people entered into a deep, complex and transformative relationship with a non-human external object. Statues of Christ, such as this thirteenth-century, life-sized polychrome wooden Spanish image (now in the Chicago Art Institute), were the focus of a passionate erotics of devotion in the middle ages:

photo credit: A.CurrellI love the bold way in which Seaman imagines the human-Christ symbiont as a posthuman self avant la lettre: "a hybrid that is a more developed, more advanced, or more powerful version of the existing self." This suggests to me – though Seaman does not argue this – that in becoming one with the non-human prop of Christ, medieval persons extended their capabilities and were in turn profoundly transformed by that encounter, in a manner analogous to modern forms of distributed cognition: their minds, in other words, did not end with their bodies but were imaginatively and practically enmeshed in, and extended by, the external tool of Christ.The medieval historian Caroline Walker Bynum asks, "Are we genes, bodies, brains, minds, experiences, memories, or souls?" (2001, 165), but this misses the point. We are all these things, but we are also – and always have been, according to the cognitive philosopher Andy Clark – more than these things. We are all these things plus the non-biological technologies (writing, computers, cellphones, Christ) that enable us to adapt to our changing environment and to better survive as humans: we are, in Clark's words, "natural-born cyborgs" (and see further my essay: Our Cyborg Past: Medieval Artificial Memory as Mindware Upgrade, postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies 1/2 (2010), 64-71). Think not so much of the woman with a cochlear implant as the woman sitting in Starbucks with an iPad – or (as I will develop here) the medieval Christian joining with Christ.I'm not thinking of the physical ingestion of Christ's body in the Eucharist but rather of the many devotional and meditative practices – imitatio Christi [imitation of Christ – the emulation of his suffering, for example], embracing and kissing statues of Christ, meditating on his body – through which medieval people entered into a deep, complex and transformative relationship with a non-human external object. Statues of Christ, such as this thirteenth-century, life-sized polychrome wooden Spanish image (now in the Chicago Art Institute), were the focus of a passionate erotics of devotion in the middle ages: Rupert of Deutz, a twelfth-century monk, imagined himself standing before the altar contemplating an image of Christ that almost seems to come alive before him: "I beheld him, living, in my mind's eye … I took hold of he whom my soul loves, I held him, I embraced him, I kissed him lingeringly. I sensed how gratefully he accepted this gesture of love, when between kissing he himself opened his mouth, in order that I kiss more deeply" (cited in Robert Mills, Suspended Animation, 2004, 177).Deutz's experience of the image coming alive is not uncommon in monastic literature. Byzantine icons of the Crucifixion were also made to elicit an emotional response from viewers and to encourage them to enter into the narrative as if actually present at the event, as in this description by the twelfth-century Byzantine writer Michael Psellos: "as the [divine] force moved the painter's hand … he showed Christ living at his last breath … at once living and lifeless." Living and lifeless: the flickering between animate and inanimate captures something of the bodily and yet thing-like aspect of the icon. If we can get past the sensational, affective erotics of Deutz's man-Christ encounter, we can appreciate its cognitive aspects: Christ is not just an external object that is used to achieve selfhood but enters into Deutz's mind and merges with it, becoming part of its own reflexive process.Some medieval statues of Christ even had jointed, moveable limbs, to increase their tractability for the embracer, like this Italian jointed crucifix in the Bode Museum:

Rupert of Deutz, a twelfth-century monk, imagined himself standing before the altar contemplating an image of Christ that almost seems to come alive before him: "I beheld him, living, in my mind's eye … I took hold of he whom my soul loves, I held him, I embraced him, I kissed him lingeringly. I sensed how gratefully he accepted this gesture of love, when between kissing he himself opened his mouth, in order that I kiss more deeply" (cited in Robert Mills, Suspended Animation, 2004, 177).Deutz's experience of the image coming alive is not uncommon in monastic literature. Byzantine icons of the Crucifixion were also made to elicit an emotional response from viewers and to encourage them to enter into the narrative as if actually present at the event, as in this description by the twelfth-century Byzantine writer Michael Psellos: "as the [divine] force moved the painter's hand … he showed Christ living at his last breath … at once living and lifeless." Living and lifeless: the flickering between animate and inanimate captures something of the bodily and yet thing-like aspect of the icon. If we can get past the sensational, affective erotics of Deutz's man-Christ encounter, we can appreciate its cognitive aspects: Christ is not just an external object that is used to achieve selfhood but enters into Deutz's mind and merges with it, becoming part of its own reflexive process.Some medieval statues of Christ even had jointed, moveable limbs, to increase their tractability for the embracer, like this Italian jointed crucifix in the Bode Museum:

photo by: Allison WucherSuch jointed statues appear almost mechanical: pieces of technology, not real persons. Wealthy individuals in the middle ages owned portable images of Christ that could travel with them or be worn as jewellery, so that they could be constantly looked at and touched, much as we carry around our iPhones and laptops. What medieval subjects experienced when they joined themselves to Christ was directly analogous to our sensation of oneness in being closely joined to our technology – and to our sense of being bereft when that technology goes missing or breaks down because it has, profoundly but almost imperceptibly, become a part of ourselves. Thinking about the medieval human-Christ symbiosis through a cyborg lens explains not only the intensity of that relationship but also why the separation from Christ is experienced as so agonizing.

photo credit: GaelleryThe medieval practice of mediation on images of the crucified Christ shares some affinities with the dissociative techniques of yoga and hypnosis that Clynes and Kline identify as having the potential to transform the body so that it can function as a "self-regulating man-machine system" in an alien environment. The medieval world was not of course space and it was not "non-natural," but it was nevertheless a harsh environment. The repeated practice of monastic and private devotional meditation enabled an almost automatic (because habitual) uncoupling from the external environment. The locus classicus of this Christian ideal of negation is St Augustine's imagining of a silence so complete that "the very soul grew silent to herself and by not thinking of self mounted beyond self," a silence in which "He alone spoke to us … and if this could continue, and all other visions so different be quite taken away, and this one should so ravish and absorb and wrap the beholder in inward joys that his life should eternally be such as that one moment of understanding for which we had been sighing - would not this be: Enter Thou into the joy of Thy Lord?" The fourteenth-century anonymous English Cloud of Unknowing recommends a program of advanced spiritual exercises that are (with some important qualifications) the medieval equivalent of yoga or hypnosis: a divesting of the mind of all images and concepts through an encounter with a "nothing and a nowhere" that leads to mystical union with God.Although The Cloud author argues that the follower of its method needs grace to complete the exercises - which isn't quite what Clynes and Kline had in mind when they spoke of a regulatory mechanism that is automatic and unconscious – nevertheless the medieval model offers a way of overcoming the physical limitations of the body through dissociation. To see medieval ascetic practices such as fasting, meditation on the body of Christ, and contemplation as cyborg technologies is to see them differently: not as a rejection of the body and a privileging of the soul/mind, but as highly developed forms of distributed cognition that combine body, mind and external technologies in a continuous and semi-automatic feedback loop.This is one of 50 posts about cyborgs a project to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coining of the term.

photo credit: GaelleryThe medieval practice of mediation on images of the crucified Christ shares some affinities with the dissociative techniques of yoga and hypnosis that Clynes and Kline identify as having the potential to transform the body so that it can function as a "self-regulating man-machine system" in an alien environment. The medieval world was not of course space and it was not "non-natural," but it was nevertheless a harsh environment. The repeated practice of monastic and private devotional meditation enabled an almost automatic (because habitual) uncoupling from the external environment. The locus classicus of this Christian ideal of negation is St Augustine's imagining of a silence so complete that "the very soul grew silent to herself and by not thinking of self mounted beyond self," a silence in which "He alone spoke to us … and if this could continue, and all other visions so different be quite taken away, and this one should so ravish and absorb and wrap the beholder in inward joys that his life should eternally be such as that one moment of understanding for which we had been sighing - would not this be: Enter Thou into the joy of Thy Lord?" The fourteenth-century anonymous English Cloud of Unknowing recommends a program of advanced spiritual exercises that are (with some important qualifications) the medieval equivalent of yoga or hypnosis: a divesting of the mind of all images and concepts through an encounter with a "nothing and a nowhere" that leads to mystical union with God.Although The Cloud author argues that the follower of its method needs grace to complete the exercises - which isn't quite what Clynes and Kline had in mind when they spoke of a regulatory mechanism that is automatic and unconscious – nevertheless the medieval model offers a way of overcoming the physical limitations of the body through dissociation. To see medieval ascetic practices such as fasting, meditation on the body of Christ, and contemplation as cyborg technologies is to see them differently: not as a rejection of the body and a privileging of the soul/mind, but as highly developed forms of distributed cognition that combine body, mind and external technologies in a continuous and semi-automatic feedback loop.This is one of 50 posts about cyborgs a project to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the coining of the term.